At present all stents used commercially or in the non-research setting are made of a metal alloy. Most commonly this is either stainless steel, cobalt chromium or platinum chromium.

All of these alloys are essentially biologically inert, meaning that they do not promote an immune reaction from your body or artery (i.e. the stent is not rejected).

Stents are used to treat coronary artery narrowings which in the majority of cases are due to a significant build-up of cholesterol plaque.

For many patients a coronary stent is used for the treatment of angina and provides significant symptomatic benefit.

For other patients, stents are used in more unstable clinical scenarios such as in a patient having an acute heart attack, where the stent is used to keep open an artery which has recently blocked.

Stent placement

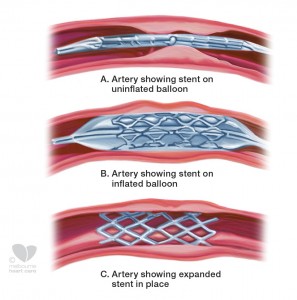

The stent is placed in the coronary artery using the same technique as that used for a balloon angioplasty procedure. The interventional cardiologist will place a small tube or catheter via an artery in the groin (femoral artery) or wrist (radial artery) to the heart. Through this catheter a small wire is placed down the artery containing the narrowing or blockage and the wire is passed through the affected region.

In most cases, a small balloon is then placed over the wire into the narrowed segment and used to gently stretch the narrowing partly open. Following this a stent is then passed over the wire into the narrowed segment and “deployed” or expanded. Once the stent has been expanded or deployed in the narrowed segment it will remain in this position indefinitely to keep the affected artery open and restore an appropriate amount of blood flow to the heart muscle.

At times during the angioplasty and stenting procedure (particularly during balloon or stent inflation) you may experience mild chest discomfort which is usually transient.

Some patients may require more than one stent placement particularly when treating multiple narrowings and this may be done during the one procedure or sometimes during a second or third procedure.

Types of stents

Broadly, stents are divided into bare metal or drug-eluting stents and this refers to whether or not the stent is coated with a drug which is designed to minimise the risk of “restenosis”.

Whenever a stent is placed in a coronary artery a healing response is triggered and the surrounding tissue will proliferate to cover the stent to a variable degree.

In some instances, this proliferation or healing response is excessive and results in significant re-narrowing within the stent. In this scenario, the patient’s symptoms such as angina may return. This process is referred to as restenosis or re-narrowing.

Drug-eluting stents were developed to try and minimise restenosis and do so by releasing a small concentration of anti-proliferative drug from the surface of the stent to the surrounding tissue. Thus the amount of tissue which proliferates and grows within the stented segment is lessened.

Following my stent procedure

In most cases the patient can resume normal activities within days after their procedure.

All patients will need to take blood thinning medication (antiplatelet medication) for a minimum period of 30 days following coronary stenting. This usually consists of two medications combined; aspirin and clopidogrel, or aspirin and prasugrel

For patients who receive a bare metal stent, a minimum period of 30 days of both of these medications (dual antiplatelet therapy) is required. For patients who receive a drug-eluting stent, we currently recommend at least 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy.

The reason for a longer duration of dual antiplatelet therapy with drug-eluting stents is that it takes longer for the cells lining the arterial wall (endothelial cells) to fully cover the metal struts of a drug-eluting stent than in the case of a bare metal stent.

Blood clots are far less likely to form within any stent once the metal struts of the stent have been covered with endothelial cells. This occurs after about two weeks in the case of a bare metal stent but in some cases may take several months with drug-eluting stents. For this reason we currently recommend extended dual antiplatelet therapy in the setting of a drug-eluting stent implantation.

It is particularly important following stent implantation to continue your blood thinners unless advised otherwise by your cardiologist. Sometimes you may be asked to stop one or both of your blood thinners for non-cardiac related procedures such as dental work, and in this instance you should always check with your cardiologist whether it is safe to do so.